Saturday 25th November sees us back at the gorgeous Mini-Cini for a triple bill of classic British horror movies all celebrating their 50th anniversary this year – Vincent Price revenger THEATRE OF BLOOD, folk horror classic THE WICKER MAN and twisty ghost story DON’T LOOK NOW.

Tickets are going fast and they’re only £7.50 each so don’t miss out!

Over to you Steve..

“Martin Scorsese has been the target of much Marvel fanboy ire of late, in the wake of multiple click-baity online non-stories, all centring around what he might or might not have said about superhero movies in general, and Marvel movies in particular. Ignoring for a moment the fact that people interviewing one of the world’s greatest living filmmakers ought to have better things to be asking him, the point he was making was clearly less about the films themselves than what they represent, the paradigm shift they signal. Some of this is in terms of how they are made, the increasing reliance on greenscreen and CGI, which has now gotten to the point where one of the principal bones of contention in the recent SAG-AFTRA strike was the use of digital imaging to replace actors or minimise their involvement in films.

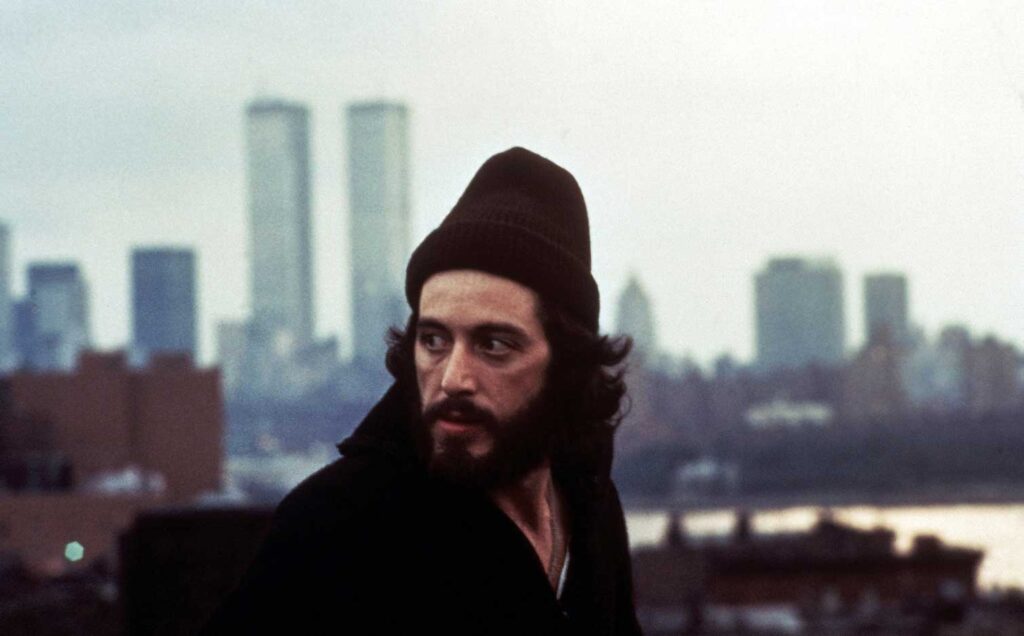

But Marty is also, of course, bewailing a cultural shift, which accounts for all of the “OK, Boomer!” responses out there. Consider, though, the cinematic landscape into which MEAN STREETS was released; the films that also came out the same year. 1973 is one of THE great years for Cinema, right the way across the globe, from the arthouse to the grindhouse, from unassailable cornerstones of the Cinema Canon, to cult classics, in every single conceivable genre. In the USA, Marty’s masterwork was jockeying for position alongside George Lucas’ AMERICAN GRAFFITI, Terence Malick’s BADLANDS, Robert Altman’s THE LONG GOODBYE, Peter Bogdanovich’s PAPER MOON, John Milius’s DILLINGER, Robert Aldrich’s THE EMPEROR OF THE NORTH POLE, Hal Ashby’s THE LAST DETAIL, Woody Allen’s SLEEPER and Ralph Bakshi’s HEAVY TRAFFIC.

Peckinpah explored (anti)heroism and (self-)mythology in PAT GARRETT & BILLY THE KID. Clint Eastwood proved implacable and unstoppable in both MAGNUM FORCE and HIGH PLAINS DRIFTER. Sidney Lumet examined the psychological damage wrought by police work on both sides of the Atlantic in SERPICO and THE OFFENCE. Truffaut laid bare the trials and tribulations of the filmmaking process in the mischievous DAY FOR NIGHT, Fellini offered a bittersweet wryly nostalgic semi-autobiography in AMARCORD, Lindsay Anderson delivered a scabrous state of the (British) nation satire in O LUCKY MAN, Paul Verhoeven and Rutger Hauer scandalised the normally unflappable Dutch with TURKISH DELIGHT and Jean Eustache took provocative potshots at French sexual politics in THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE.

It was a great year for genre, too. The boundaries between arthouse cinema and the fantastic started to grow increasingly blurred in Jodorowsky’s visionary THE HOLY MOUNTAIN, Wojciech Has’ startling THE HOURGLASS SANATORIUM, and Victor Erice’s VOICE OF THE BEEHIVE, in which a young Ana Torrent is haunted by the spectre of Frankenstein’s Monster. There were seminal crime movies such as THE OUTFIT, THE FRIENDS OF EDDIE COYLE, THE SEVEN-UPS and CHARLEY VARRICK. Martial arts movies ranged from ENTER THE DRAGON to LADY SNOWBLOOD. It was the year of Blaxploitation classics GANJA & HESS, COFFY, THE MACK, and SCREAM BLACULA SCREAM, while Roger Moore debuted as James Bond in the Blaxploitation-influenced LIVE AND LET DIE, which would prove his best outing in the role.

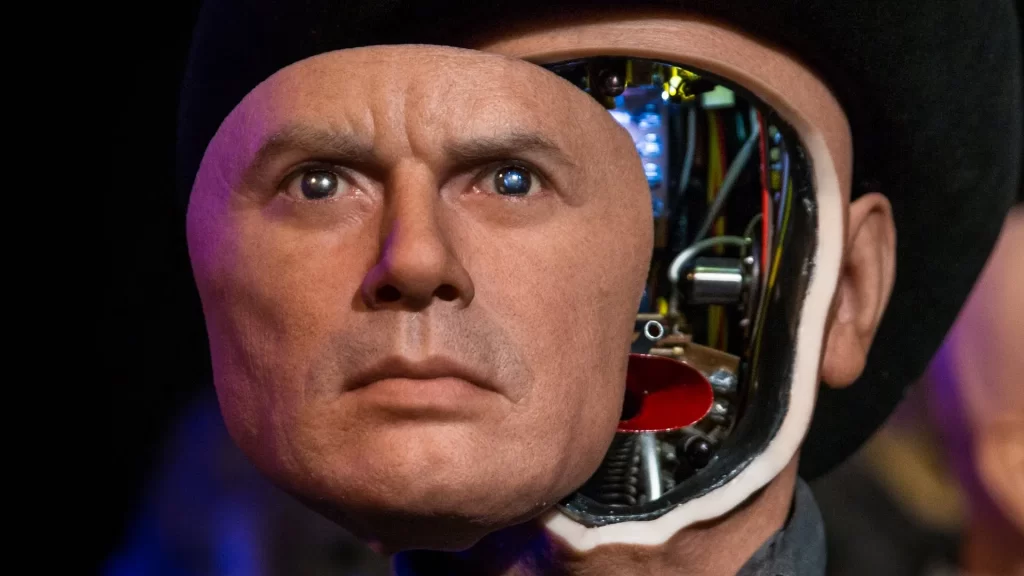

It was a truly bonanza year for the Cinema of the Fantastic. John Philip Law, Caroline Munro and Tom Baker confronted some of Ray Harryhausen’s finest creations in THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. James Brolin and Richard Benjamin were stalked by Yul Brynner’s dead-eyed robotic gunslinger in WESTWORLD, Chuck Heston discovered the questionable ingredients of SOYLENT GREEN, and there was a BATTLE FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES. Jess Franco gave us Lina Romay as THE BARE-BREASTED COUNTESS and Jean Rollin presented THE IRON ROSE. Above all, it was a year of truly seminal horror cinema. Udo Kier demonstrated disgusting sexual fetishes in Paul Morrissey’s FLESH FOR FRANKENSTEIN, George Romero savaged Small Town America with THE CRAZIES, Ted Post exploded the nuclear family in the queasily unsettling THE BABY, and the haunted house made a comeback in John Hough’s full-blooded film of Richard Matheson’s modern gothic classic THE LEGEND OF HELL HOUSE.

And, then, of course, there was Hurricane Billy Friedkin’s blistering, no-holds-barred film of William Peter Blatty’s THE EXORCIST. Not so much a horror film as a cultural phenomenon; an unstoppable cinematic juggernaut crammed with contemporary fears and folk devils with Old Nick himself at the wheel, combining thought-provoking theology and philosophy with bone-chilling thrills, and barnstorming grande guignol spectacle in one of the year’s most must-see movies. Closer to home, Amicus paid portmanteau homage to E.C. Comics in VAULT OF HORROR. And that great tradition of British Cinematic Gothic continued to deliver elegant chills in THE SATANIC RITES OF DRACULA, THE CREEPING FLESH and AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS.

A truly remarkable double bill hit British Cinema Screens, as Nic Roeg’s DON’T LOOK NOW was tandemed with (a then sadly-truncated version of) Robin Hardy’s THE WICKER MAN. The subsequent half-century has seen both films establish themselves both as genre classics, and as masterpieces of the cinema form. They also both expose the recently-coined concept of “elevated genre” for the specious nonsense it is. Horror has always dealt with serious issues – all be it with varying degrees of seriousness – and serious filmmakers have always been drawn to it as a result. And just as Friedkin and Blatty were blowing the doors off in the USA, Hardy and Roeg were doing the same in the UK.

THE WICKER MAN is the quintessential culture-clash folk horror, combining rambunctuous folk music, sly satire and mischievous black comedy, with a suffocating sense of escalating dread, and offering in the process an astute, balanced, and extremely slippery examination of conflicting values and morality, and the seductive power of comforting mythologies and ideologies however false and fraudulent they might eventually prove. It is a film which feels more relevant than ever before in our current post-Brexit climate. DON’T LOOK NOW is as technically and visually astonishing now as it was on its first release; a kaleidoscopic, time-fragmented study of grief, guilt, and a collapsing marriage in the eerie limnal landscape of Venice. Unsettling and disorientating, authentically chilling, emotionally devastating, and ultimately both heart-stopping and heartbreaking, it’s long been a favourite among the

Grimmfest Team.

We really couldn’t let the 50th Anniversary of such a genre-shaking double bill go unmarked. So we are offering a chance to relive it, albeit with both films now presented in fully restored form. And, as icing on the cake, we are adding a third 1973 genre classic to the mix: Douglas Hickox’s mischievous and malicious high-camp horror comedy, THEATRE OF BLOOD, in which Vincent Price’s vengeful ham actor carries out a truly Shakespearean revenge on his hated critics. On the surface, this might seem an unusual choice; far more in keeping with the established tradition of gaudy English Gothic established by Hammer, Amicus and Tigon, than the ostensibly more serious approaches to genre demonstrated in THE WICKER MAN and DON’T LOOK NOW. And, yes, this is one reason for the film’s inclusion: it does offer a snapshot of the British genre film landscape of the time. But it would be wrong to see this as a case of “business as usual”. Price’s creatively vengeful antagonist, cutting a swathe through a cast of much-loved British theatrical and character acting talent, might seem at first simply a riff on his role in Robert Fuest’s much-loved Dr Phibes movies. But for all of its jeu d’esprit sense of fun, this is a smart and literate film, which knows its Shakespeare, and the world of the English Theatre; a film which targets long-established British snobbery about genre cinema, indeed about cinema in general, by reminding us all of the levels of violence and cruelty that appear in the works of our greatest playwright. It is also a beautiful showcase for and homage to the inimitable Vincent Price, who actually began his acting career on the London stage before returning to his native USA and Hollywood stardom, a fact which gives added weight and emotional resonance to his performance here; a glimpse, perhaps, of an alternate life he could have lived.

In short, three genre-redefining films, from one of the greatest years in cinema history. Fifty years on, and their influence remains undiminished. And that kind of cinematic impact, good people of the internet, was what Marty was actually talking about.”