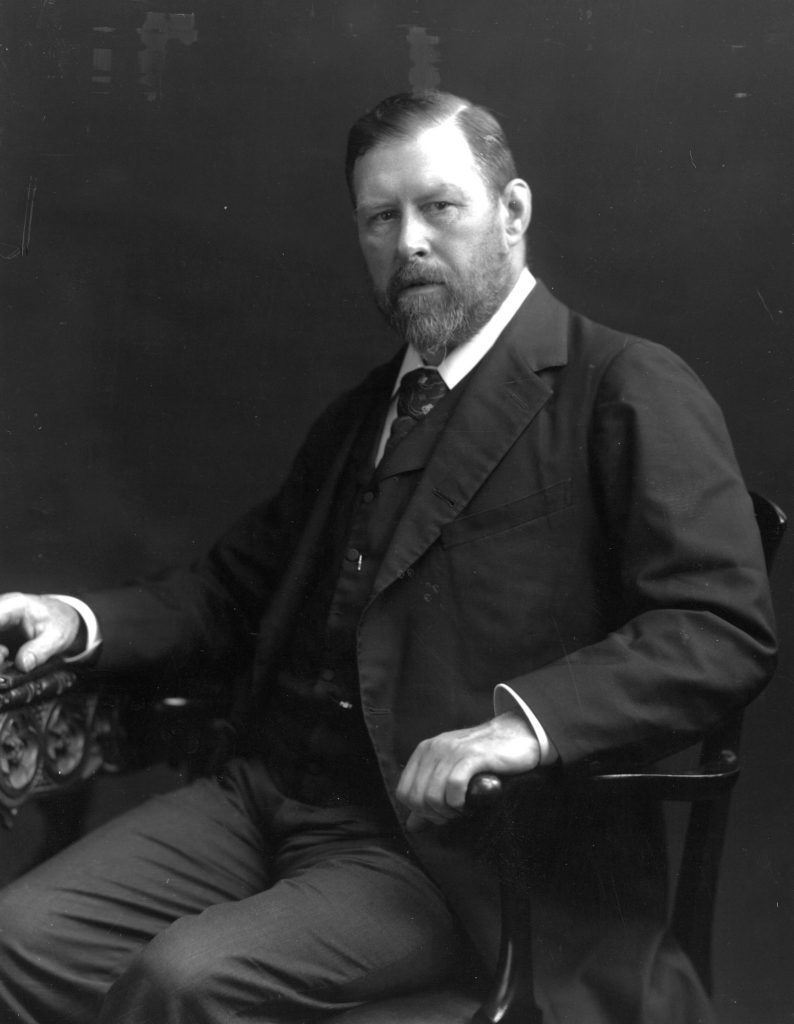

2022 is the 30th anniversary of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (click the link to buy tickets for our screening on Friday 8th July!) and also the one hundred and tenth anniversary of the death of Bram Stoker himself, creator of one of horror’s most enduring characters, that bloodthirsty Transylvanian nobleman, Count Dracula.

Our chief film programmer and excellent wordsmith Steve Balshaw has composed an amazing piece celebrating Bram Stoker and his influences and legacy.

Fill your chalice with fresh blood, settle back and dive in.

Over to you, Steve…

“Stoker was neither the first to introduce vampire lore into English literature, however, nor the first to create an enduring vampire archetype. Dr John Polidori’s The Vampyre had unleashed the Byronic Lord Ruthven on Georgian England as early as 1816. Between 1845 and 1847, James Malcolm Rymer had thrilled mid-Victorian audiences with the lurid serialised adventures of the amoral Sir Francis Varney in the epic Varney The Vampyre or The Feast of Blood, and Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu had created literature’s second most notable vampire, Mircalla, Countess Karnstein, in Carmilla in 1872, a full 25 years before the Count first donned his opera cape.

Prior to his authorship of Dracula, Stoker was best known for his literate, perceptive theatre criticism, and for his roles as business manager at the Lyceum theatre and personal assistant to its owner, the actor / manager Sir Henry Irving. He had published four previous novels, all of them fairly mainstream romances, and none of them particularly notable or successful. Nothing in his literary output would have led anyone to expect that he had any flair for the supernatural. And yet Stoker was somehow able to create the quintessential vampire tale; the one that all others reference and defer to.

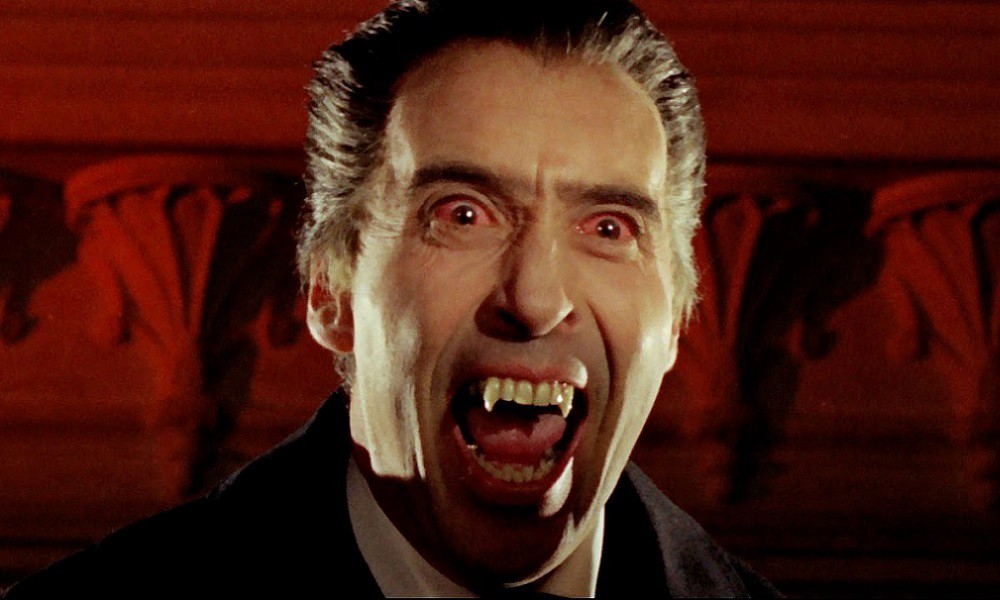

Dracula very quickly overshadowed its predecessors and continues to do so to this day. First published in 1897, the novel was an immediate best-seller, and in the 125 years since then, has been adapted and reinterpreted literally hundreds of times, for theatre, film, radio, television, comic books, and animation.

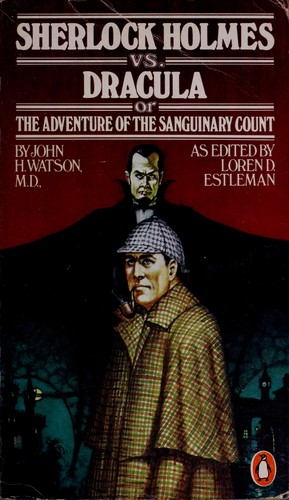

There have been numerous spin-offs and sequels, ranging from Robert Lory’s sequence of pulp paperbacks back in the 1970s, to a recent, “official” sequel, Dracula The Undead, penned by Stoker’s own great grand-nephew, Dacre, in partnership with screenwriter Ian Holt. There have been various alternative re-tellings and re-imaginings of the story, such as Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian, Tim Lucas’ The Book of Renfield, or Roderick Anscombe’s The Secret Life of Lazlo, Count Dracula, while Kim Newman, in Anno Dracula and its various follow-ups, opts for droll, post-modern mischief, repositioning Dracula as a figure at the very heart of 20th Century life and culture. This position is undeniable. Dracula has become the definitive vampire archetype; an iconic, instantly recognisable figure, referenced, parodied, pastiched and paid homage to in a myriad different ways, from Grandpa Munster to The Count in Sesame Street, to adverts for toothpaste. He has done battle, over the years, with Jack the Ripper, Sherlock Holmes, Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Blade, various costumed superheroes and even the garishness of 70s fashions. He has become a brand name.

It seems cruelly ironic, then, that this anniversary, when we should be celebrating Stoker’s achievement, should fall at a time when the popular image of the vampire has become so… well… toothless. The effect of Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight sage, Charlaine Harris’s Sookie Stackhouse books, and all of those other so-called “Dark Romances” cluttering up the shelves at Waterstones has been to reduce the vampire to a kind of pallid bad boy outsider emo-goth dreamboat for spotty teenaged girls to moon over. Vampires have gone from being dangerous bloodsucking sexual predators to wimps and whiners; pouty, pretty, pasty-faced, and awash with arrested-adolescent angst. It would be a brave writer indeed who tried to write a seriously scary vampire novel in the current climate.

Diehard vampire fans may gnash their teeth in frustration and fury, but it may well be that they are themselves partly to blame for this shifting paradigm. After all, it’s a shift that has been coming for quite a while. It is as evident in the novels of Anne Rice and Poppy Z. Brite as it is in the various emotional entanglements of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and the brain-numbingly repetitive vamp-porn of Laurel K. Hamilton’s Anita Blake books. The simple fact is that as soon as the vampire became a focus for erotic-romantic fantasies – no matter how dark and disturbing those fantasies might initially have been – it was only a matter of time before those same fantasies went mainstream, became a part of popular culture. And in the process they got dumbed down, sanitised and robbed of any sense of danger. It is the same process that saw the dark, disturbing gothic romances of Ann Radcliffe and the Brontes flayed and filleted to provide the tropes and templates for a multitude of moribund Mills and Boon and Harlequin paperbacks.

The irony is that, due to Stephanie Meyer’s disturbed and disturbing attitude to sex, the Twilight books, despite all that they have done to debase the vampire archetype, are actually more in keeping with the traditions of vampire mythology and literature than many far more respected modern horror novels. Vampires have always been used to represent the dangerous sexual “other”, and thus to explore fears and anxieties about sex and sexuality. Seductive, decadent and ambiguous, the vampire is the personification of Bad Sex and Unhealthy Attitudes. Of something dark, and dangerous and socially unacceptable.

It is therefore entirely appropriate that the first vampire to appear in English Literature, Lord Ruthven, in Dr John Polidori’s novella, The Vampyre (1816), should have been inspired by the author’s onetime friend and employer, the poet, rake, and professional controversialist, George Gordon, Lord Byron. Byron was a man who enjoyed, indeed revelled in his own notoriety, courting public condemnation and outrage by word and deed, scorning received opinion, stirring things up wherever he went. He had already been depicted, unflatteringly, under the name Lord Ruthven, in the novel Glenarvon (1816), by his former lover, Lady Caroline Lamb, who famously described him as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know”, and so, when The Vampyre was first published, featuring a character of the same name, it was widely attributed to Byron himself. Spawned from the same Lake Geneva ghost story “contest” that also produced Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the novella’s depiction of an alluring, utterly amoral, vampire nobleman clearly chimed with public perception of “The Bad Lord Byron” to such an extent that it was perceived as a typically outrageous, controversy-courting piece of self-dramatisation. The novel’s lasting importance, however, is in establishing the archetype of the vampiric aristocrat. It also, by the simple fact of its real-life associations, makes the figure of the predatory vampire and the Romantic, (in this case literally) Byronic antihero virtually synonymous in the public imagination.

This popular image of the vampire was consolidated, and extensively built upon, by James Malcolm Rymer. Rymer is a highly influential, yet largely unsung figure in the history of horror fiction. Though his name remains obscure, his characters, and many of his ideas, imagery and narrative tricks have entered into popular culture. Sweeney Todd, the “Demon Barber of Fleet Street”, first appeared in Rymer’s novel The String of Pearls, and while the bloodsucking Sir Francis Varney lacks the iconic status of the author’s best known creation, his contribution to the shaping of modern vampire mythology cannot be underestimated. Varney The Vampyre, or The Feast of Blood, was first published between 1845 and 1847 as a series of cheap “Penny Dreadful” pamphlets, and runs to an epic 1166 close-printed pages in the modern paperback collected edition. Lurid, sensational, often crudely and clumsily written, its rambling and digressive narrative more focused on presenting a series of thrilling, chilling, and gruesome incidents than a consistent, carefully-structured story, the novel nevertheless is the root source for many now-standard vampire tropes and traditions. Here we first encounter the familiar figure of the vampire’s cringing human henchman or familiar, the torch-and-pitchfork-bearing villagers, the midnight visit to the family vault to lay one of the undead to rest. Sir Francis Varney has fangs, and leaves twin puncture wounds on the necks of his victims. He is revived repeatedly from apparent death, but is weary of his eternal existence. He is also the first truly sympathetic vampire, who sees his condition as a curse to be raged against, and wishes to end it. He is, in short, more Byronic even than Lord Ruthven. He is also, like Stoker’s Dracula (and unlike the later film versions) able to go out in daylight, eat and drink normally, and generally masquerade as an ordinary, mortal, human being.

Stoker’s other main literary influence was, strangely enough, his former employer; Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, co-owner of the Dublin Evening Mail, where Stoker had launched his career, as the paper’s Theatre Critic. Le Fanu was a master of eerie, elegantly-written, atmospheric, gothic horror fiction and ghost stories, highly influential in the evolution of the genre. And, in his novella Carmilla, he created possibly the most iconic vampire character after Dracula. Carmilla is the story of a young English girl, Laura, who lives with her retired father in Styria, and longs for a female companion her own age. A carriage accident outside the castle where she lives delivers the secretive and mysterious Carmilla into her life. The two become close friends, but Carmilla sleepwalks and before long Laura is troubled by dreams of a great black cat-like creature feeding on her blood at night. Then she discovers a portrait of one of her ancestors, Mircalla, Countess Karnstein, who has an unnervingly close resemblance to her new friend…

Le Fanu adds several elements to the vampire narrative that clearly influenced Stoker. His vampire, like Dracula, is a shape-shifter. She seduces her victims, playing on their emotional and sexual needs, as Dracula does Lucy Westenra. Le Fanu is also the first writer to make a direct analogy between vampirism and what he perceives as “sexual abnormality” – Mircalla is the archetype of the predatory lesbian vampire. Le Fanu also influenced Stoker in his use of a real-life historical figure to add weight, colour and credibility to his creation. Just as Le Fanu drew on the gory legends surrounding the real-life figure of Elizabeth Bathory, the “Blood Countess”, who was accused of torturing and killing dozens of young women, and bathing in their blood in a bid to remain young, so Stoker drew on those of Vlad III, Prince of Wallachia, variously known as Vlad Tepes (Vlad the Impaler) or Vlad Draculea (Vlad the Dragon) for the name and some of the background of his bloodsucking Carpathian Count.

However, while it is easy enough to identify the influence of earlier authors on the development of Dracula, one should not underestimate Stoker’s own achievements. He may lack the exotic Byronic connections of Polidori, the gory sensationalism of Rymer, or the elegant, evocative prose of LeFanu, but he does have a remarkable talent for synthesis. His theatrical and newspaperman’s background clearly instilled him with strong instincts for what was most dramatic. In Dracula, Stoker skilfully draws on, and cherry-picks from, the various earlier vampire narratives to create something, if not entirely original, then certainly far more potent and affecting than what had gone before. He deftly blends his variously-appropriated elements, expanding upon certain already-established tropes and traditions, throwing in a few new ones of his own, and bolts them all into a fast-moving, gripping narrative. Just as the Penny Dreadfuls of James Rymer found their way into the heady mix, so, too, did the popular and rather more literary “Sensation Novels” of the 1860s and 1870s. Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White (1859), with its charismatic, charming, and, yes, aristocratic villain, Count Fosco, and, more importantly, its multiple perspective first person narration, compiled from the journals, diary entries and letters of the various characters, must surely have provided a structural model, though Stoker takes it still further, even incorporating at one point the supposed transcript of a “Phonograph diary”.

The featuring of a phonograph recording at a key juncture is highly significant. Stoker makes very conscious use of throughout the novel of the latest scientific developments, from new modes of transport to the blood transfusions given to Lucy Westenra in an attempt to save her life. The novel offers a very clear conflict between the clear (gas) light of the modern, scientific, Western world and the superstitious darkness of the supernatural world. Dracula may draw on ancient myths and legends and on the traditions of Gothic and Sensation fiction, but Stoker is keen to emphasise that this is a modern novel, set in the modern world. As such, it can be read as a comment on that world. And on the people inhabiting it.

Stoker had learned a valuable lesson from Dr John Polidori: the importance of tapping into popular opinion; of using his own associations in his favour, and suggesting links between his creations and certain controversial public figures of his acquaintance. There is nothing most people like more than prurient gossip about a celebrity…

The role model for Dracula is usually said to have been Stoker’s sometime employer, Sir Henry Irving, and it is certainly the case that Stoker derived certain of the Count’s physical characteristics and mannerisms from Irving. But this, I think, is all. The main inspiration lay elsewhere. On its initial publication, Dracula was dedicated to Stoker’s close friend, the Manx writer Hall Caine. This dedication is not simply an act of friendship, but the acknowledgement of a literary debt.

A best-selling novelist in his day, Caine is now best remembered as a friend and early biographer of one of the more outlandish and controversial figures of his age, the painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti. At heart a gentle, generous, outgoing man, Rossetti was transformed by neurosis, paranoia, and hypersensitivity to criticism, into an isolated, insomniac recluse, about whom increasingly bizarre and baroque rumours flourished. In earlier years, he had consciously encouraged such rumours, playing up to the role of eccentric artist, filling his home with exotic trinkets and artworks from all over the world and giving free reign to a menagerie of exotic animals, from armadillos to wombats, Brahma bulls to boxing kangaroos. But in later years, Rossetti’s life really did begin to resemble the plot of a gothic horror novel. When his young wife, Elizabeth Siddal died of a (possibly deliberate) drug overdose in 1862, he was so overwhelmed by grief and guilt that he buried the only existing manuscript of his as yet unpublished poems with her. Seven years later, fearing that his eyesight was failing, and he would no longer be able to paint, he was persuaded to have the poems exhumed from the coffin, so he could revise and publish them. The grisly facts of the exhumation were largely kept a secret during his lifetime, although dark rumours persisted, but Rossetti was haunted by what he had done, claiming that Siddal visited him every night for the rest of his life.

Hall Caine was the first person to make this story public. His Recollections of Rossetti, published only months after Rossetti’s death in 1882, contains a lurid account of the exhumation, including the somewhat improbable claim that:

“…the body was apparently quite perfect on coming to the light of the fire on the surface and …when the [manuscript] book was lifted, there came away some of the beautiful golden hair in which Rossetti had entwined it.”

An exhumation, a body untouched by death, a dead woman who is nevertheless seen every night by the man she loved. Stoker must surely have had this story in mind when creating the narrative of Lucy Westenra in Dracula. Lucy, Lizzie – even the names are similar.

Then, too, there is the close resemblance between Caine’s account of his first visit to Rossetti’s home at 16 Cheyne Walk and that of Jonathan Harker’s account of his arrival at Castle Dracula: Night-time; a forbidding, run-down building; not a servant in sight, only the odd, elusive master of the house there to greet his increasingly nervous guest. The parallels are obvious enough, and I am not the first to have noticed them: Anyone wondering why there are armadillos pottering about Castle Dracula in the Tod Browning / Bela Lugosi film might be interested to learn that Rossetti kept several in his menagerie.

Dracula’s physical appearance, it is true, owes more to the tall, gaunt, hawkish Irving than to the balding, overweight, slope-shouldered Rossetti, but Rossetti did have the intense, hypnotic eyes and commanding, persuasive voice Stoker ascribes to the vampire. Living virtually alone, a recluse, refusing all visitors, sleeping during the day and only going out, if at all, at night, Rossetti even had a tendency to wear big cloak-like coats and tinted glasses on the rare occasions he did venture outdoors. He had already been the likely model for the charming, charismatic, amoral Count Fosco in one of Stoker’s key influences, The Woman In White (Wilkie Collins knew Rossetti through his brother, Charles Alston Collins, who had been a member of the original Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood and an unsuccessful suitor of Rossetti’s sister, Maria), and for the sinister painter (and manipulative emotional vampire) Walter Hamlin in Vernon Lee’s 1884 feminist gothic novel Miss Brown (which, like Dracula, had drawn on elements of J Sheridan LeFanu’s Carmilla ). What is more, Rossetti had a direct family connection with the first vampire to appear in English fiction – his mother, Frances, was the sister of Dr John Polidori. All of these factors surely attracted Stoker to Rossetti as a model for his sinister vampiric count.

It is not simply elements of Rossetti’s life and personality that influenced Stoker in the writing of Dracula, however, but what he represented. A child of Italian immigrants, Rossetti was viewed by hostile critics as essentially “un-English” in his approach to art; a “foreigner”, importing unwholesome attitudes and values from the Continent. His dense, complex verse, with its rich fusion of metaphysical symbolism and frank eroticism was widely criticised as decadent, “fleshly”, somehow “unmanly”. His intense, lushly-rendered images of tall, gaunt, haunted-looking women with bee-stung lips and pale long-fingered hands offered a new type of female beauty; strong, powerful, sensual, dangerous; a direct contrast, almost a rebuke to the diminutive, submissive unthreatening ideal of the time. Women perceived as “bad” in late-Victorian fiction are almost invariably described in a manner that suggests a Rossetti painting. Stoker probably had one such painting in mind when creating the character of the flighty, ill-fated Lucy Westenra.

Sinister “foreign” villains have a long history in English popular fiction, and the Victorians seem to have been particularly fond of them. But the 1890s does seem to have been particularly rife with such characters. In addition to Dracula (1897), there was Svengali in George Du Maurier’s Trilby (1894), the evil master-criminal and mad scientist Dr Nikola in Guy Boothby’s A Bid For Fortune (1895), and the (quite literally) Satanic Count Lucio in Marie Corelli’s The Sorrows of Satan (1895). All have their origins in the racial paranoia and immigration phobia of the era. Following various state-sponsored Pogroms in Eastern Europe, England – and in particular the East End of London – found itself faced with a huge influx of what today would be termed Asylum Seekers. Then, as now, there was much talk in the popular press about “floods of foreigners” with habits and cultural values entirely unlike our own Levels of hostility became so extreme that there were attempts to attribute the 1888 Jack the Ripper killings to East European Jewish immigrants. Stoker very consciously taps into such paranoid fears: Dracula arrives from abroad hidden in a crate in the hold of a ship – exactly like an illegal immigrant. And immediately he begins to seek out victims. Female victims. He could thus almost be seen as a living embodiment of contemporary fears of decadent foreigners seducing virtuous Englishwomen.

But there were other fears at play here.

Though the sensuality and frank emotional eroticism of Rossetti’s paintings and poetry were seen as decadent, effeminate, and unmanly, he was nevertheless heterosexual. A number of his circle, however, would certainly have offended the sexual morals of the day. The painter Simeon Solomon was gay, the poet Algernon Swinburne was a sadomasochist. Rossetti was widely seen as the central figure in a whole school of equally degenerate artists and writers, and a truly unhealthy influence on all.

And influential he most certainly was, not only upon those in his immediate circle, but on the generation of artists and writers who followed.

The Aesthetic Movement of the 1890s revelled in its opposition to the prevalent social mores of the age. Their attitude was one of (self)-consciously adopted bored moral and sexual ambivalence; celebrating artifice over nature and art for its own sake, devoid of context; almost wilfully decadent in their choice of subject matter; deflecting criticism with droll wit and an affectation of indifference. A self-elected artistic and literary avant-garde, centred around the quarterly periodical The Yellow Book – which derived its name from the plain yellow paper in which supposedly lascivious French novels were bound – they took their cues from precisely the kind of debauched and sinister foreigners that everyone else seemed so afraid of.

Foremost among them was Oscar Wilde. While many of the others seemed content to remain outsiders, Wilde took the attitude and values of the Aesthetes right into the mainstream. And then, in 1895, it all came crashing down around his ears, as he found himself on trial for homosexuality. Nowadays, such a trial seems grotesque, barbaric. But at the time it was a major national scandal, revealing the existence of a sexual underworld that seemed to be occupied by a great many powerful and influential people. Added to existing fears about “sinister foreigners flooding the country” was a new fear about a growth in what was then perceived as “sexual abnormality”. Thus we have the shape- and gender-shifting – and of course foreign – eponymous antagonist of Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897), using his mesmeric powers to seduce men and women alike. And we have Dracula.

It is worth noting that the novel was first published on May 26th 1897, precisely one week after Oscar Wilde was released from prison, and it is tempting to see a connection; to see in Wilde another possible model for the charismatic and predatory count. After all, the association of vampirism with sexual ambiguity was a central element of the novel’s most immediate source, Le Fanu’s Carmilla, and although Dracula himself favours female victims, he does make Renfield into his cringing slavish familiar, and comes very close to preying on Jonathan Harker, in scenes rife with sexual overtones. The novel might thus seem to be a reaction to the social anxieties stirred up by the recent trial, and the figure of Dracula thus essentially a folk devil designed to play on contemporary homophobia as well as racist paranoia.

But there is a problem with such a reading. Stoker and Wilde were friends. They had known each other as students in Dublin. They had both courted the same woman, Florence Balcombe, who Stoker married in 1878, but they did not fall out over this, nor did Stoker reject Wilde following his fall from grace – indeed he visited him in exile on the Continent. If Stoker did incorporate elements of Wilde into Dracula, then surely his intention cannot have been to attack or demonise a friend he stuck by even when that friend became a pariah. Similarly, when considering the other models for Dracula, it must be remembered that Stoker greatly respected and admired Sir Henry Irving, and while Stoker’s knowledge of Rossetti was derived second hand from his close friend Hall Caine, it is worth noting that Caine idolized Rossetti.

Perhaps herein lies the source of Dracula’s longevity in comparison with the other books cited above. It is more challenging than it first appears. While Stoker dramatises and plays up to the racial and sexual anxieties of his age, he does not necessarily share them. Perhaps he is trying to explore his own feelings, his own deepest-felt anxieties. More than one critic, noting the novel’s emphasis on male bonding and apparent suspicion of female sexuality, as well as his continued friendship with and support of Wilde, has argued that Stoker was gay, albeit heavily-closeted, and that the novel is a coded plea for tolerance. Well, maybe. What is certain is that, for all of its fast-paced, thrill-ride sensationalism and ultimately reassuring narrative trajectory, in which the status quo and the values of the age are ultimately reaffirmed, Dracula has an ambivalence at its very heart: the figure of the Count himself, complex and multilayered, ambiguous and seductive, transcending the novel that spawned him, seizing his own place in the popular imagination for ever after.

Of course, there could be another, far simpler explanation for Dracula’s pre-eminence among vampire characters, as well as for the way in which the character seems so quickly to have broken free of the narrative restrictions of the eponymous book in which he first appeared. Stoker failed to follow proper copyright procedure, meaning that, while it was protected in Europe until 1962, under the Berne Convention on copyrights, in the USA the novel has always been in the public domain. Anyone and everyone could adapt the book however they liked, could make use of the character, in whatever context. And you need only look around you to see that they did, and continue to do so. Unleashed from any one person’s control, Dracula was free to become an archetype. And thus he has become truly unstoppable.”

Join us at Mini Cini on Friday 8th July to watch BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA on the big screen along with 30 DAYS OF NIGHT!