Steve Balshaw, GRIMMFEST’S head programmer celebrates the work and mourns the loss of a cinematic creative force and an inspiration to us all in the world of genre cinema.

Lynch has become a name; and that name has become an indispensable adjective.

We can describe something as “Lynchian” in the same way as we might term it “Dickensian”, or “Shakespearean”, or “Kafkaesque”, and everybody immediately knows what is meant by that. Which, right there, puts him in some pretty august company; suggests his absolute uniqueness as a creative force. Because there are very few film-makers ever to have been accorded this honour. Hawks, Fellini, maybe Frank Capra. But not Welles, not Godard, not Eisenstein, nor Ozu, nor Kurasawa. Not even John Ford, who Lynch himself recently portrayed onscreen for Steven Spielberg. And certainly none of Lynch’s own contemporaries.

There are plenty of filmmakers who could claim auteur status, all of them with instantly recognisable voices and vision, all of whom have the capacity to take the viewer to new places, new realms of experience. But very few of them are world-builders the way Lynch was; very few can create the kinds of hermetically sealed universes he could; utterly unique and idiosyncratic, absurd and nightmarish, dark and disorientating, but filled with a deadpan sense of mischief, finding the creepiness in kitsch, and the silliness in surrealism. It’s a very knowing and self-aware cinematic world, but it never stoops to sniggering or nudging the viewer hard in the ribs to draw attention to that fact. It offers the viewer no ironic distance by which to insulate themselves, which is why it continues to unsettle so deeply.

That, and the fact that Lynch’s world really is unlike anything else. Many years ago, sometime in the mid-80s, he made a documentary about surrealism in cinema for, I think, the BBC, in which he talks about the early surrealist filmmakers and their influence on his work. And, yes, it’s possible to see that, particularly in his early shorts such as THE ALPHABET (1969) and THE GRANDMOTHER (1970). But ERASERHEAD (1977) is something else again. ERASERHEAD is a film that seems to have no precedent, that comes from nowhere, and shakes up the cinematic world forever. Was its sulphurous, oppressive, Expressionist / Surrealist spin on family life born out of his own anxieties about fatherhood, as has been claimed? Or was it more inspired by, and intended to satirise, the sanitised, stylised, depictions of family seen in the soaps and sitcoms of 60s TV? Both interpretations have been offered; neither really accounts for what is onscreen. Nothing, really, accounts for what is onscreen. It announces an entirely new voice, distinctive and original, and utterly uncompromising, and establishes many of the recurring themes and visual tropes that will characterise that voice in the years to come.

So it’s all the more startling that he should follow such a disturbing, disorientating debut, a cult film among cult films, with a UK-based costume drama, filled with top-tier British thesps, and produced by, of all people, the King of Comedic bad taste himself, Mel Brooks. But this is of course precisely what he did, and very much on his own terms, too, with Brooks running interference for him against the increasing alarmed money men. The result, THE ELEPHANT MAN (1980), based on the extraordinary, tragic true story of John Merrick, won multiple awards, and brought his unique cinematic sensibility right into the mainstream, without a single compromise being made. In many respects, Lynch’s most immediately accessible, and certainly his most emotionally engaging – and devastating – film, it nevertheless remains true to the vision established in ERASERHEAD, reimagining the oppressive industrial landscape (and accompanying soundscape) in the setting of Victorian London. The end result is about as far from the comforting costume dramas and limp literary adaptations of Merchant Ivory and the BBC Sunday evening drama serial as it is possible to get, while, at the same time, managing to appeal to the same audience, as well as to those looking forward to the follow up to his first feature.

And it established Lynch at once as an A-List director, a white-hot, exciting new talent, much in demand, offered the big projects and the big budgets. And all of the big studio crap, the compromises and rewrites, the recuts and re-edits, the domineering producers and panicking money men that go with that, and which Brooks had protected him from during THE ELEPHANT MAN. The end result was DUNE (1984). Widely derided at the time, financially a bit of a disaster, it’s been considerably reassessed over the years, and now occupies the position of “interesting failure” or “flawed, forgotten gem”. Or some such faintly patronising term. And yeah, it’s frankly a bit of a mess, filled with flashes of what might have been had Lynch’s vision been less compromised, had the producers not tried to cram all of Frank Herbert’s epic novel into a single feature film, and then insisted on cutting the best part of an hour out of the end results. What remains, though, is never less than entertaining, like some mad hybrid of STAR TREK and LAWRENCE OF ARABIA. And it forged a bond between Lynch and the actor who would go on to become a kind of cinematic Alter Ego from this point on, Kyle MacLachlan.

Which of course brings us to the film that really established the Lynchian worldview in the wider public consciousness; the film that would influence other, lesser filmmakers ever after, the twisted, tonally slippery, genre-blurring, still startling and shocking BLUE VELVET (1986). A nightmarish neo-noir comedy of manners and social mores, alternately hilarious and horrifying, absurd and alienating, set in some tweaked, timeless, alternative universe version of small-town America, where the white picket fences do not disguise the riot of rot and ravenous insects beneath, it takes the darkness that underlies the sentimental social dramas of Frank Capra, and the sourness that infects the soapy romantic melodramas of Douglas Sirk and runs with them, stirring in more than a pinch of Kenneth Anger’s ritualised kitsch, to offer a devilish deconstruction of the comforting Norman Rockwell myths America tells itself, as the narrative turns ever darker, more grotesque, but also more absurd, as the increasingly eccentric, stylised performances, and deliberately ridiculous bits of artifice (that clockwork songbird!), threaten to derail the entire film into broad farce. It’s a truly uncomfortable cinematic experience, from Dennis Hopper’s terrifying yet hilarious off-the-chain performance as the psychotic Frank Booth, to Dean Stockwell’s showstopping, “so fucking suave” cameo as Ben, mining all of the underlying malevolence and dark desperation in the lush, yearning balladry of Roy Orbison. It’s regarded as a modern classic now, but people tend to forget just how controversial it was at the time, both in its apparent eroticisation of sexual violence, and in its seeming unwillingness to ultimately take the emotive and morally challenging issues it raises entirely seriously. Or perhaps the point is simply that the attempt, at the end, to reassert “normal” values is intended to seem just as artificial and ersatz as that clockwork songbird.

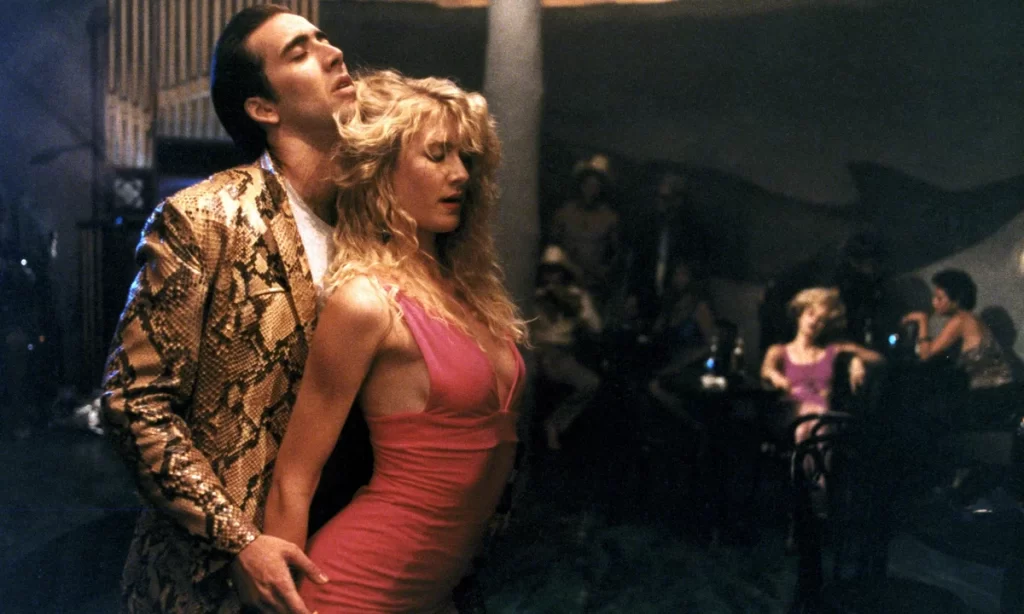

The film very much set the tone, and consolidated most of the tropes and themes that would recur in Lynch’s work from this point onwards. TWIN PEAKS (1989 – 91) saw him essentially expanding on the world(view) he’d established in BLUE VELVET, and, what is all the more remarkable, doing so on US Network TV, with little to no compromises. At the time, the show was described as a surreal spin on PEYTON PLACE, the long-running TV soap inspired by the 50s feature film adapted from Grace Metalious’s torrid trash classic novel about the sleazier side of small town America, but it probably owes as much to much-loved cult show, DARK SHADOWS, in the way it mashes together soap operatic intrigues with full-on American Gothic. In some ways, the series is Lynch’s most outrageous act of subversion, in that it masquerades as a mainstream crime investigation / mystery series, with elements of small-town soap opera, but continually challenges and deconstructs the established tropes and traditions of such shows, refusing easy answers, pat solutions, understandable character arcs to a degree which amounts almost to self-sabotage as the series progressed to a second season, and the narrative and character twists became ever more baroque and bizarre. Game changing and envelope-pushing, TWIN PEAKS still stands as a watershed moment in TV history, and its influence has echoed on down the years, impacting upon everything that has been done ever since riding high on the success of TWIN PEAKS, and now very much established as both an A list director and a pop-cultural phenomenon, Lynch made a triumphant return to the cinema, and found a new creative collaborator in novelist and maverick film noir maven Barry Gifford, whose novel, WILD AT HEART, he adapted in 1990 into a ferociously unflinching and riotously romantic road movie, expanding on the themes and slyly post-modern genre savvy self-awareness of the source novel, while stirring in various obsessions of his own. Boasting a truly terrifying turn from Diane Ladd, a show-stealingly sleazy and seedy cameo from Willem Dafoe, and a lead couple with genuine onscreen chemistry and, well… heat, in Laura Dern and Nicholas Cage, it is also, more than any other film, responsible for establishing Cage’s… unique… screen persona, and he’s been ringing the changes on it ever since.

The film was a huge critical and commercial success, consolidating Lynch’s already considerable reputation. He was in a position to do anything he wanted. And what he wanted to do, it seems, was return to the world of TWIN PEAKS, in the feature film sequel / continuation / reinvention, FIRE WALK WITH ME (1992). Perhaps he had felt some sense of limitation working for Network TV, even surrounded by sympathetic creative collaborators and long-term colleagues, and wanted to take the material to a darker place than the restrictions of mainstream US TV would ever permit. Or perhaps he simply wasn’t finished with the world he had created there, and wanted to explore it further, as he would go on to do again, many years later in TWIN PEAKS’ much-belated “Third Season”.

He might also have been exorcising some of his issues with the nature of Network TV production in his and Mark Frost’s follow-up to TWIN PEAKS, ON THE AIR (1992). A truly demented Lynchian spin on the “backstage comedy” sitcom, purporting to depict events behind the scenes of THE LESTER GUY SHOW, an oddball, anachronistic parody of early 60s show drama anthology series THE DICK POWELL THEATER, it starred PEAKS alumnus Ian Buchanan as Lester, with Kim McGuire (best known as Hatchetface in John Waters CRY BABY), and oddball character actor Tracy Walter, and was so gleefully uncategorisable and stubbornly uncommercial that, of the seven episodes made, only 3 ever aired on US TV (The BBC screened them all, but, as I recall, late night and out of sequence).

It was the kind of bridge-burning stunt that would have made a pariah out of most people, and it did seem to briefly stall Lynch’s thus far ever-upward career trajectory. It was a full five years before his next feature, the evocatively titled LOST HIGHWAY (1997), another collaboration with Barry Gifford, this time working from an original screenplay. A smart, slippery, self-reflexive surrealist neo-noir, riffing shamelessly off Robert Aldrich’s KISS ME DEADLY, and with multiple nudges in the ribs and nods to other genre classics, it’s both a thrilling, knowing homage to a much loved genre, and a truly nightmarish exploration of alienation and fragmenting identity.

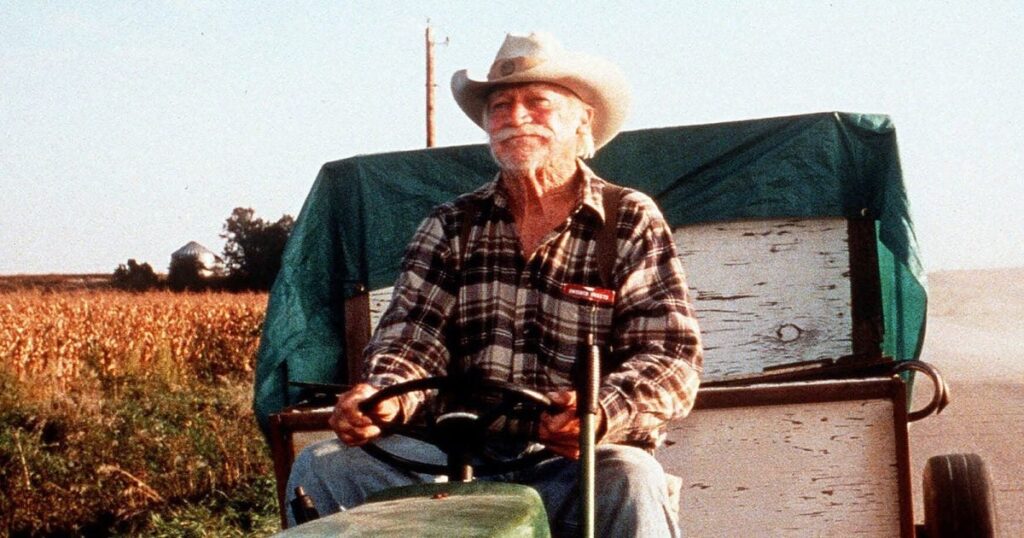

The urban landscapes and neon-lit roads of LOST HIGHWAY were replaced by the dusty plains of Iowa, for THE STRAIGHT STORY (1999). A gentle, meandering road movie in a minor key, it sees Lynch channelling his inner Capra for an unexpectedly heartwarming, but admirably unsentimental tale of perseverance and filial love, based, however loosely, on the true story of one Alvin Straight, an old man dying of emphysema who rode across country on a motorised lawn mower to make peace with his estranged brother. Featuring the extraordinary final performance of former stuntman turned character actor Richard Farnsworth, and beautifully judged support from Sissy Spacek and Harry Dean Stanton, it’s a film filled with charm, warmth, and real-life eccentricity, as strange and surreal as anything that appears elsewhere in his work. The fact that emphysema would eventually be the disease that killed Lynch himself gives the film a newfound poignancy and pathos.

But if Lynch had hoped the film might open new doors for him as a family friendly filmmaker, this never materialised, because the same year as THE STRAIGHT STORY, he began work on MULHOLLAND DRIVE, a sour and cynical Hollywood noir, building on some of the themes and tropes explored in LOST HIGHWAY, but this time riffing off a very different cinematic source of inspiration than KISS ME DEADLY; Jacques Rivette’s French New Wave cult classic, CELINE AND JULIE GO BOATING, already the inspiration for DESPERATELY SEEKING SUSAN, but here reworked and repurposed into an exploration and deconstruction of female noir archetypes. Conceived initially as the pilot film for an ongoing TV series, the project stumbled and stalled, only to be picked up again, and redeveloped and expanded for cinema release a couple of years later.

Looking back at reviews and interviews with Lynch from the late 90s, early 2000s, it soon becomes clear that each new film was seen by critics as a redeclaration of creative purpose a re-establishing of his filmmaking credibility after several years of skirting close to self-parody, of performing an increasingly consciously contrived version of himself, as Hollywood’s loveable oddball and eccentric. Because, by this point, Lynch’s public persona was well and truly established, carved in stone, almost; “Jimmy Stewart from Mars”, as Mel Brooks famously described it. That honking, MidWestern twang, the gnomic pronouncements, pitched somewhere between Buddhist and Dali, the increasingly flamboyant hairstyle. It was a persona seemingly as carefully constructed as that of Andy Warhol, right down to a similar taste for black polo necks, and it served him well in the years ahead. He could be himself, or he could perform as himself, and people would not be disappointed, because the eccentricity, performative or not, fit right in with the films themselves. And as it became increasingly difficult to get feature films funded and made, he could always fall back on the performance, on simply BEING DAVID LYNCH. There were music videos and concert films for performers as diverse as (frequent collaborator and muse) Julee Cruise, Nine Inch Nails, Marilyn Manson (who had appeared in LOST HIGHWAY), and, God help us, Duran Duran. There were glossy adverts for high-end products. There was a comic strip at one point, THE ANGRIEST DOG IN THE WORLD. And there were multiple shorts, some barely seen. There were books, paintings, exhibitions, he even tried his hand at carpentry. He kept following his creative mojo, wherever it might lead him. He never for one moment stopped being an artist.

And every so often he’d get a chance again at something bigger. INLAND EMPIRE (2006), his final feature film as it turned out, and almost 20 years old now, reunited him with Laura Dern, for a dizzying, disorientating mindfucking meditation on performance and actorly (self-)obsession, shot in a deliberately grainy, grimy, uncomfortably intimate Dogme95-influenced style on (largely handheld) digital cameras; it alienated as many of his admirers as it enthralled, which was surely the point. And then, just when it seemed his career would peter out amid a few retrospectives and amusiing guest appearances and the occasional advert or music video not really worthy of his talents, there was that final, glorious return to the world of Twin Peaks, reclaiming it, reimagining it, using it to deliver one last uncompromising statement of creative purpose and intent. It’s the kind of comeback so very few artists ever get to make. And the greater and more uncompromising they are, the less likely they are to have the opportunity.

But David Lynch went out on top. He went out swinging.

Inimitable, incorrigible, irreplaceable. Utterly sui generis. We will never see anything quite like him again. And that’s a damn tragedy, right there.

R.I.P.,David Lynch. May your coffee never go cold, may your cup never be empty, and may the wild birds sing for you.